On Tuesday, Uber drivers took part in strikes organised by the App Drivers and Couriers Union (ADCU) meanwhile the Independent Workers of Great Britain (IWGB) Union are planning for more Uber drivers to strike on the 6th October. Additionally, IWGB’s Deliveroo and UberEats members have organised numerous strikes and demonstrations over the past five years. In fact, the Leeds Index of Platform Labour Protest estimates that globally between January 2015–July 2019 there were 324 protests by platform workers.

Protest such as Tuesday’s raise the question of why it is that work in this sector is so contentious? This is the question that the iLabour Project investigates in two new articles. The first is a qualitative article published by the journal Socio-Economic Review,‘Antagonism beyond employment: how the “subordinated agency” of labour platforms generates conflict in the remote gig economy’, based on 70 interviews with workers in the remote gig economy and participant observation of gig worker community events. The second is a quantitative article ‘Dynamics of contention in the gig economy: Rage against the platform, customer or state?’ published in the journal New Technology, Work and Employment and which uses a survey of 430 Upwork and PeoplePerHour workers in the remote gig economy. Workers in the remote gig economy usually work fronm their homes and carry out tasks related to things like digital marketing, search engine optimization, virtual assistance, writing, and design.

When we think of workers engaging in collective actions, whether it be strikes, demonstrations, or other forms of resistance, we usually think of employees in factories in the heavy industries taking action against their employer. So it’s perhaps surprising that here we find self-employed workers and freelancers taking action too. But such workers do not have traditional employers and instead protest in a manner of ways variously against digital platforms, customers, and the state.

Remote gig workers protest against platform fees.

In theory, these freelancers shouldn’t need to protest, as they have the option to vote with their feet and exit any situation they find unsatisfactory simply by finding new customers to work with. In fact, we find workers do just this when faced with clients who mistreat or disrespect them and workers saw themselves as dealing on an equal business–to–business footing with their customers. As Julie who worked as a copywriter in LA explained:

“I’ve had some clients… [where] it was just the last straw and I was like, why am I dealing with this pain, this stress?… So like I cut ties… You always have the option of firing [the client].”

In order to understand why workers didn’t act in a similar manner towards platforms required us to first investigate platform businesses models in the gig economy. Platforms operate as multi-sided markets and a feature of such markets is that demand across both sides is interdependent: the more clients there are, the more useful the platform is for workers, and vice versa. This dynamic is called network effects and can lead markets to ‘tip’ towards monopoly. Additionally, data collected by platforms on their users can lead to data lock-in by increasing the costs of leaving the platform. These factors along with the fact that platforms often use contractual means to buttress their gatekeeper position mean that the ability for workers to exit a platform is often limited. As Chris who carried out digital marketing work in LA explained:

“Most people I know dislike [GigOnline]… you use them because you have to… they purchased platform X… [and] platform Y and consolidated… no one has any other option. I tried to get [in] to FreelanceOnline but that sucks even more. So they got me back on GigOnline.”

But gig economy firms also act as market organisers. This means that they don’t just provide the digital infrastructures that enable actors to connect and contract with one another wholly as they please – they also manage growth on both sides of these markets, for instance by subsidising one side with fees charged from the other side. They also provide tools that help clients to identify and contract suitable workers and vice versa. In other words, platforms maintain the necessary social order for transactions to take place. In doing so platforms enact their authority over users through the creation and enforcement of rules.

We show how the combination of platform dependence and platform authority results in a relationship of subordination that workers cannot easily exit but in which platforms still grant workers significant agency to contract with a diverse pool of clients beyond their local labour market. We term this situation where workers experience enhanced agency towards clients but also subordination towards the authority of a platform upon which they are dependent ‘subordinated agency’. It is this subordinated agency that leads gig workers to experience antagonism with the platform as a structural feature of their relationship – one that cannot be remedied via exit due to platform dependency. Our research highlights that this antagonism can manifest as conflicts over the rates offered on platforms, the fees platform’s charge, and the way they deny workers a voice. As Gabe who undertook digital marketing tasks in Manila argued:

“We’re earning less and less… because the platform that we’re using is taking away twenty percent from us… if it stays this way, the freelancing industry… [will] turn into slavery or sweatshop.”

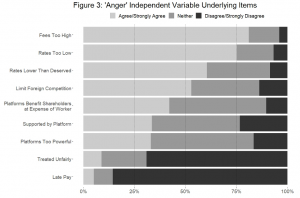

Indeed our quantitative research found that grievances over the fees that platforms charge workers, the pay they receive, and the level of competition they face were widespread among our survey respondents. Moreover, workers faced considerable dependency and insecurity with more than 75% fearing that the platform would increase the fees they charge workers and 62% worrying about the effect of unfair customer feedback on their future income. Large minorities of the workers we surveyed also thought platforms were too powerful (24%) and that they benefit shareholders at the expense of workers (42%)

This antagonism in turn led workers to support collective organisation and even unionisation as a means for countering the power that platforms wielded over their ability to make ends meet. This support for unions surprisingly existed despite workers overwhelmingly identifying as self-employed freelancers engaging in businesses–to–business relations with their clients. As Gemma who worked as a writer and script editor in Liverpool explained:

“You have to stand up and go, we’re not gonna do this anymore. So I’m surprised there isn’t a union as such for freelancers, which sounds [like] an anomaly. You know, a freelancing union. But there should be because it needs to be regulated more. In a way, it’s slave labour. It’s slave labour every day for freelancer writers, fighting, trying to find work through platforms like GigOnline and OnlineGigs because it’s just is not a fair marketplace at all.”

But to understand why workers undertake actions aimed at different targets (customers, platforms and the state) we have to turn to our quantitative data. By running multiple regressions, we can see that whether workers support state regulation and minimum wages for platform work is predicted by their sense of being treated unjustly by platform companies. However, those workers who engage in individual actions against customers tend not only to be angry about their treatment at the hands of these companies but also to be engaging in communication with other platform workers. This is because such action can be risky and, therefore, the solidarity of other workers is important as it provides the social capital (knowledge and moral support) necessary for workers to feel confident in standing up to customers. Incidentally, we find that digital communication between these workers is widespread with 45% communicating through either social media or online forums at least once a week. But the 50% of workers who said they would join a trade union or workers’ association for freelancers tended not only to be angry at their treatment and be communicating with other workers but also highly dependent on their main platform. This in turn made unionisation a particularly attractive remedy to injustice for these workers despite the potential high individual costs entailed in setting up effective unions.

While we only investigated the origins of antagonism and conflict in the remote gig economy we highlight that the concept of subordinated agency could also be fruitful for explaining conflict in the local gig economy as well as the platform economy more widely. You can read the full articles here:

‘Antagonism beyond employment: how the “subordinated agency” of labour platforms generates conflict in the remote gig economy’ https://academic.oup.com/ser/advance-article/doi/10.1093/ser/mwab016/6375544?searchresult=1

‘Dynamics of contention in the gig economy: Rage against the platform, customer or state?’ https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/ntwe.12216

without a paywall https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/8nm37/