Digital labour platforms have become a pervasive feature of contemporary society. They allow us to order food, arrange a ride, or buy remote freelancing services online. But how are they transforming the world of work? The International Labour Organisation (ILO) has just released its annual flagship report, which this year focuses on platforms. ILO researchers, led by Dr Uma Rani, collaborated with the iLabour project team led by Professor Vili Lehdonvirta at the Oxford Internet Institute on parts of the report that focus on remote platform work, also known as online freelancing and online gig work. In this post, we will highlight some of the report’s findings.

Remote software and tech gigs increase

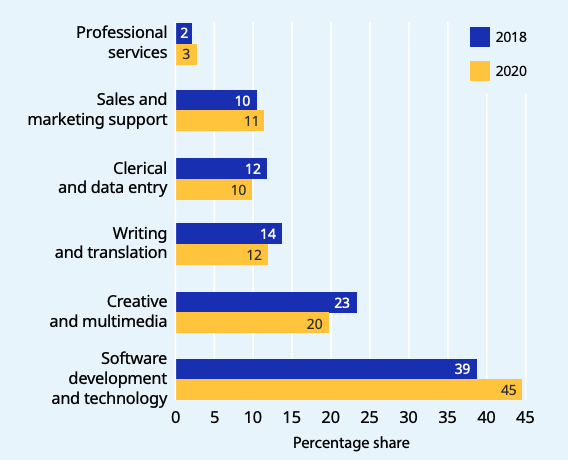

Figure 1: The share of online labour tasks performed in software development and technology work has increased from 2018 to 2020. Source: ILO World Employment and Social Outlook 2021.

Many kinds of work today are conducted remotely via online freelancing platforms. Drawing on iLabour data, the ILO report shows that the largest share of online gigs globally is in the category of software development and technology work (Figure 1). This category’s share of all online freelance work increased from 39 per cent in 2018 to 45 per cent in 2020. The relative shares of professional services and sales and marketing work have also increased, while the share of creative and multimedia work declined from 2018 to 2020. The ILO report argues that these changes may be attributable to the effects of the pandemic, which we also investigated in a recent research article.

Dominance of US employers decreases

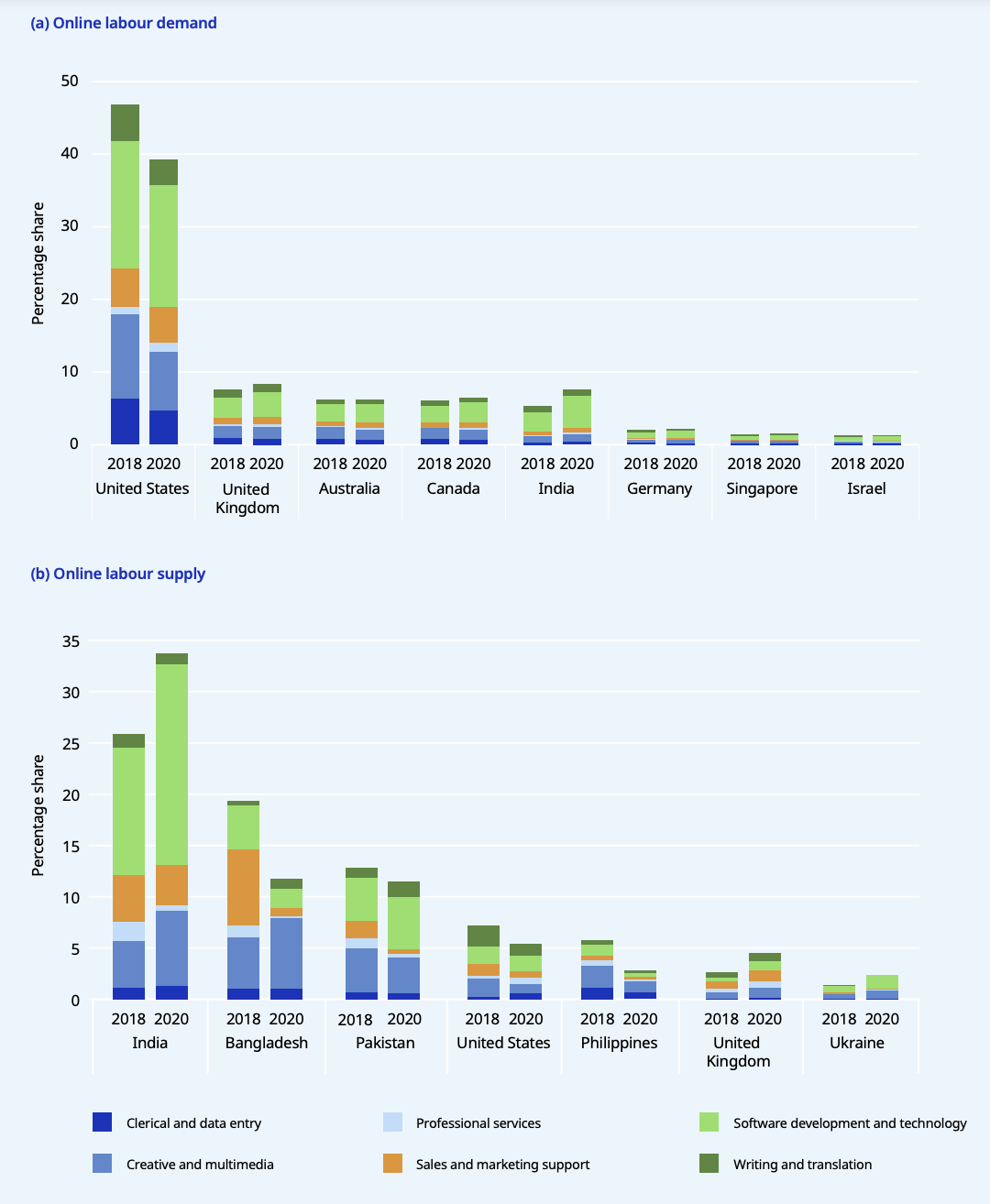

Figure 2: From 2018 to 2020, share of demand from the United States decreased while labour supply from India was on the rise. Source: ILO World Employment and Social Outlook 2021.

Figure 2a disaggregates online labour demand by occupation category and employer country. Clearly, software development and technology are the most sought-after occupations on freelance platforms across countries. The share of demand in this category has increased worldwide from 2018 to 2020. In India, the proportion of software development and tech work demanded by employers relative to other occupation categories is particularly high. US employers are buying a more even mix of different skills online.

Online labour supply from India continues to increase

While online labour demand comes mostly from the United States and other rich countries, the supply of labour on these platforms originates especially from lower- and middle-income countries. Figure 2b shows that workers from India are the largest suppliers of global online labour; India’s share of total supply rose by about 8 percentage points from 2018 to 2020, while it declined in other lower- and middle-income countries, except Ukraine. The ILO report argues that, given the large, highly educated English-speaking workforce in India, it is not surprising that the share of platform work delivered by workers in that country is substantial. According to the report, the rise in the share of total supply coming from India was driven by an increase in the share of labour supply in software-related tasks, which is consistent with the extensive offshoring of IT, BPO and software services to India.

The ILO report, titled The role of digital labour platforms in transforming the world of work, marks the start of a broader collaboration between the International Labour Organization and the Oxford Internet Institute’s iLabour team. Next week, we will be launching an Online Labour Observatory, a new digital data hub for researchers, policy makers, and the public.